Archive | June 2021

IT IS POSSIBLE TO TELL ONE BLUE JAY FROM ANOTHER

I have long been fascinated with trying to tell one individual bird of the same species from another. When it comes to some species, the only way this is possible is when one bird has an unusual feather (e.g. color, feather, injury) that distinguishes it from others of its species. In other cases, birds of the same species may exhibit slight variations in their basic color patterns. For example, a few weeks ago I posted a blog that discussed a technique that allows an observer to identify one male rose-breasted grosbeak from another by the subtle differences in their red chevrons. A similar technique allows you to tell one blue jay from another.

The blue jay is undoubtedly one of our most easily recognized birds. All blue jays seem to appear exactly alike. However, if you take the time to study the black necklace-like pattern displayed across the bird’s throat, face, and nape, it becomes apparent that this pattern varies widely between blue jays. In fact, once you begin focusing on this feature, you will wonder why you never noticed these differences throughout the many years that you have been watching the comings and goings of blue jays in your backyard.

The blue jay is undoubtedly one of our most easily recognized birds. All blue jays seem to appear exactly alike. However, if you take the time to study the black necklace-like pattern displayed across the bird’s throat, face, and nape, it becomes apparent that this pattern varies widely between blue jays. In fact, once you begin focusing on this feature, you will wonder why you never noticed these differences throughout the many years that you have been watching the comings and goings of blue jays in your backyard.

A quick way for you to appreciate this fact is to pull up a collection of blue jay photos on your computer. If you do, in a matter of seconds, it becomes apparent that each blue jay has its own unique black necklace.

If you photograph the blue jays visiting your birdbath and feeder, don’t be surprised if you discover you are hosting more blue jays than you ever realized.

BACKYARD SECRET–RUBY-THROATED HUMMINGBIRDS EAT LOTS OF INSECTS AND SPIDERS

Most hummingbird enthusiasts believe plant nectar is the primary food of the ruby-throated hummingbird. At the same time, they recognize small insects and spiders are essential to the rubythroat’s diet. However, according to entomologist Dr. Doug Tallamy, renowned native plant proponent, and a growing number of hummingbird experts, hummingbirds are actually insectivorous birds that also consume nectar. In fact, Dr. Tallamy has stated, Hummingbirds like and need nectar but 80 percent of their diet is insects and spiders.”

Research conducted by biologists at Cornell University’s Laboratory of Ornithology seem to corroborate this claim. When the researchers trapped and followed the movements of a female hummingbird for two weeks never once did she eat any nectar.

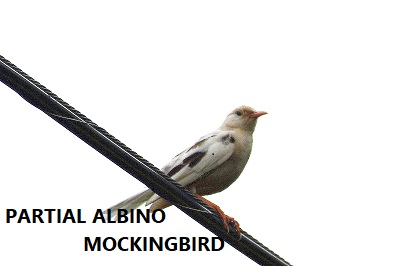

A RARE WHITE MOCKINGBIRD

Whenever a white bird shows up in a backyard it is a special event. Each year I receive from one to three reports of white ruby-throated hummingbirds appearing in backyards across the state. A few years ago, a close friend photographed a white northern cardinal visiting his feeders. In addition, many years ago a Middle Georgia couple reported a white bluebird nesting in one of their nesting boxes. However, until a few weeks ago I had never been notified of a white northern mockingbird sighting.

As you can see from the accompanying photograph, this bird is almost totally white except for a few black feathers on its wings. The bird’s feet and bill are pinkish white. However, the mockingbird’s eyes are dark.

Ornithologists might argue as to whether this bird displays albinism or leucism. However, I believe this mockingbird is a type of albino. This condition is brought about by the bird lacking any pigment called melanin.

The four types of albinism are true (sometimes referred to as total), incomplete, imperfect and partial.

A true albino’s plumage is totally white whereas its legs, feet, and bill are white to pinkish. A true albino’s eyes are always pink or red. The presence of black feathers in the same areas of both wings, and seemingly dark eyes, leads me to believe this bird is a partial albino.

Albinism has been documented among some 304 species of North American birds. Interestingly, it is most commonly occurs in blackbirds, American robins, crows, and hawks.

If an albino bird shows up in your yard, it will be an experience you will long remember. I have never seen a white bird in my yard, however, several years ago a partial albino hummingbird fed at my neighbors’ feeders. I was sure it would fly over to my feeders. However, for some reason, it never did. To have one come that close to your yard is tough to take. However, I have never given up hope I will see a white bird in my yard. Perhaps one will magically appear this year.

AMERICAN GOLDFINCHES ARE LATE NESTERS

For the last several weeks, American goldfinches have been mighty scarce around my feeders. However, last week I was surprised to see a male American Goldfinch sharing sunflower seeds with a small group of house finches. Seeing the bird in full breeding plumage was a reminder that, unlike many birds, the American goldfinch waits until spring to undergo a complete body molt. Many ornithologists believe this may be linked to the fact that The American goldfinch nest far later than most other Georgia songbirds.

According to this theory, since such a molt requires the bird to expend a huge amount of energy, it lessens its ability to nest until later in the year after their energy reserves have been replenished. In the case of Georgia American goldfinches, it is just about time for them to begin nesting.

According to this theory, since such a molt requires the bird to expend a huge amount of energy, it lessens its ability to nest until later in the year after their energy reserves have been replenished. In the case of Georgia American goldfinches, it is just about time for them to begin nesting.

The American goldfinch nesting season in the Peach State commences in late June, however, it reaches its peak in July and August. Some females will even be nesting as late as September.

These nesting habits will affect the numbers of goldfinches we will see at our feeders. Once nesting begins, during the 12-14 days the females are incubating their eggs they will have little time to feed. Consequently, during period we are likely to see males more often at our feeders than females.

DON’T FORGET TO DEADHEAD BUTTERFLY BUSHES

Butterfly bushes are truly butterfly magnets. However, if you want them to continue blooming from now until migrating monarchs pass through out state months down to road; you must deadhead the plant’s spent blossoms.

For reasons I do not understand, this spring my butterfly bushes have been covered with the largest clusters of flowers they have ever produced. Unfortunately, few butterflies were around to enjoy them. However, lots of bumblebees, honeybees, and carpenter bees constantly visited the nectar-rich blossoms while they were blooming.

Fortunately, butterfly bushes can be encouraged to produce a bounty of flowers throughout much of the growing season. All it takes is deadheading the bush’s flower clusters before they go to seed.

Recently I deadheaded my butterfly bushes for the first time this year. From experience, I know I will have to repeat this procedure many times. However, I realize that, if I am diligent, countless butterflies and other pollinators will benefit from the food produced by crop after crop of fresh flowers. In the past, I have been successful in prolonging the butterfly bushes’ blooming until the monarchs en route to their wintering home in Mexico. When they use my yard as a stopover area on their epic journey it is not uncommon to see anywhere from four to eight monarchs on a single butterfly bush.

When deadheading a cluster of flowers, remove the spent cluster down to the spot close to the point when the main flower stem joins two side branches. If this is done at the right time, the two side branches will quickly produce flowers too. When the blooms on the main branch and side branches have already turned brown simply, cut the stem just above the next juncture of side branches and the main stem.

This is definitely a case where a little time spent cutting back spent flowers will produce a beautiful bush and remain a source of nectar throughout the summer.

BACKYARD SECRET–NATIVE BEES ARE OFTEN MORE EFFICIENT POLLINATORS THAN HONEY BEES

As odd as it may sound, many of our native bees are at least three times more efficient pollinators as the introduced honeybee.

Take for example the bumblebee: many of us grow blueberries in our yards. Many pollinators including honeybees and bumblebees visit the blueberry plant’s creamy white flowers. Studies have demonstrated that a honeybee would have to visit a blueberry flower four times to deposit the same amount of pollen as a bumblebee can in only one visit.

In addition, native bees are more common than honeybees in many of our yards. Unfortunately, few honey bees visit the flowers in my yard. Luckily, tiny solitary, bumble, and carpenter bees are routinely seen visiting a wide range of flowers found there.

This summer, as you walk around your flower and vegetable gardens take note of the bees you find pollinating your flowers. If you do, don’t be surprised if you see very few honeybees and an abundance of native bees hard at work pollinating the plants that provide you with food and a cascade of beautiful flowers.

I am convinced that we are guilty of underestimating the value of the 532 species of native bees that can be found flying throughout Georgia.

HERE IS WHAT YOU SHOULD DO IF YOU FIND A YOUNG BIRD ON THE GROUND

Every year countless Georgia homeowners find helpless young birds on the ground beneath trees and shrubs. In some cases, the young birds and their nests are torn out of a tree by an intense storm. In other cases, a young bird simply accidentally falls from its nest. If you happen across such a bird, do you know what to do?

If you find a hatchling, look about and see if you can locate its nest. If you do locate it, simply place the young bird back in the nest. More than likely, parents are perched nearby and will resume raising the youngster.

On the other hand, if you find a whole or partial nest containing young, place the nest or its remains and young birds in something like a hanging basket. If the container is much larger than the nest, place the nest atop some mulch (choose mulch that will not get soggy when wet). Then hang it in the tree as close as you can to its original location.

After you have replaced the nest and young birds all you can do is wait. In the best-case scenario, the parents will return to the young. However, after a reasonable length of time, if the parents have not returned to claim their hatchlings, contact a licensed wildlife rehabilitator.

A list of Georgia’s licensed wildlife rehabilitators can be found at www.gadnrle.org. Once you open the site scroll down the subject list to Wildlife rehabilitators. These dedicated, skilled individuals are listed by county and the types of wildlife they are qualified to treat.

IT’S MULBERRY TIME!

One of my favorite times of the year is when the mulberries begin to ripen on my backyard mulberry tree. While my wife and I enjoy eating the sweet juicy berries, what I enjoy even more is watching the parade of birds that flock to the devour every berry in sight.

Yesterday, my long wait for this special event ended when I noticed the tree is festooned with berries. Although most of the berries are not ripe, I have learned that the hungry birds begin devouring the berries well before they are fully ripe.

The birds that flock to mulberries are all card-carrying members of the bird world’s Who’s Who List. While I am not a usually a name-dropper, the list of a few of the birds that eat mulberries includes bird royalty such as the eastern bluebird, rose-breasted grosbeak, great crested flycatcher, scarlet and summer tanagers, wood thrush, red-eyed vireo, northern bobwhite and wild turkey.